Description

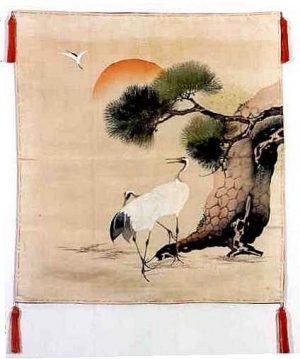

A Fukusa is a cloth, elaborately designed and commissioned by a prominent Japanese family, used to cover a gift that has been placed on a wooden or lacquered tray during the ceremonial and formal presentation of the gift. Each aspect of the ritual was prescribed by closely defined rules of etiquette laid out during the Edo (1615-1868), Shogun or Tokugawa Eras. The design was an original creation related to a specific use: a happy occasion, such as a wedding, or a form of respect for a member of one’s immediate society, such as a funeral condolence…the significance of which was was handed down from generation to generation. Thus, the Fukusa cannot be interpreted only on its artistic merit, but also needs to include its specific role in historic Japan. The practice of covering a gift was widespread before the 1900s, but because the Fukusa was closely held by the family, it is very rare to find one today. The Fukusa became a valuable family heirloom, as the family personally commissioned a Master Artist to design the gift cover, not only to be a thing of beauty, but also to represent the family’s social status. The Fukusa, itself, was not part of the gift…only part of the ritual. The use of a Fukusa was an especially common practice prior to the 1900s, although it continues to this day in certain circles in Japan.

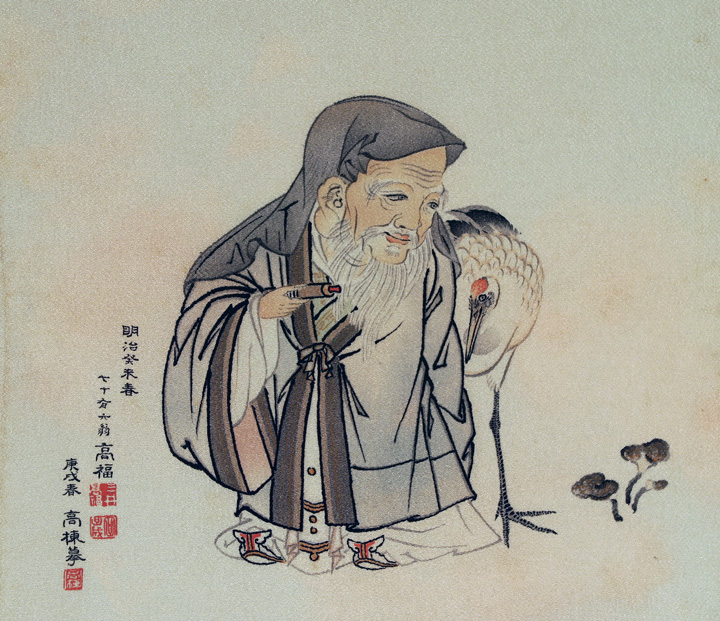

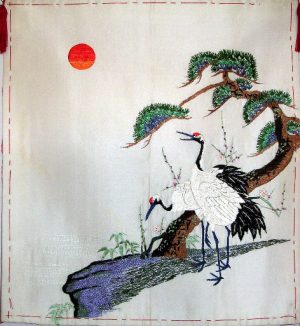

The hand painted portrait of this charming Sage is similar to the depictions of one of the Seven Lucky Gods of Japan, about which there is still considerable confusion among Japanese scholars between two of the depictions: Fukurokuju and Jurojin, or God of Wisdom and Longevity. Their association appears to come from the Chinese Taoist tradition of the hermit sage. There is also a familial connection of the two whereby Jurojin becomes the Grandson of Kukurokuju…hence, the conflict. Reinforcing the depiction as that of Jurojin is his domed head and his long white beard. Notice the sacred book tied to his staff, which is credited with containing the lifespan of every person on earth, and the accompaniment of the Crane (“Tsuru”) which has symbolized longevity for centuries. Thus, he becomes an immortal representing enlightenment and long life.

Only natural dyes were used, while the actual hand woven crepe-like Chirimen Silk incorporates an extraordinary weaving process which was limited to the wealthy; and, whose technique has been lost to the Japanese for over 100 years. It has been hand painted using the Rice Paste Resist or “Tsutsugaki” method of painting on Silk. This process required that each color be applied separately while all the others were painted out in the rice paste. Each time a new color was added; the rice paste had to be removed by soaking it out over and over again in the local river water and then reapplied. This technique required a great amount of skill by the artist as well as being extremely labor intensive. The use of the light green (“Midori”) background further reinforces the theme of life as well as the time of year; and, unlike other countries, carries no negative attributes in Japan. Green was also a difficult coloration to accomplish as there were no natural elements in Japan that would produce it. In some instances, a fabric would have to be over dyed: blue over yellow; and, in the choice of blue greens, it would be produced from natural minerals.

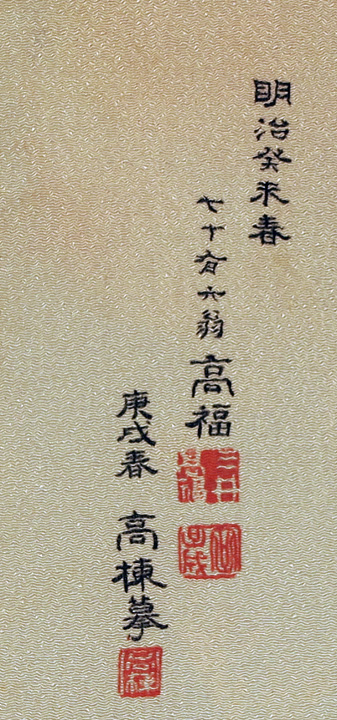

It’s unfortunate that this marvelous piece of Japanese culture is incomplete, as it makes it impossible to determine the specific family that initially had this work of art created. That the Fukusa became a valuable Japanese heirloom is completely understandable as the family itself designed, and commissioned famous artists to create a work of art in their name, demonstrated by the signature, seal, and notes of the artist prominently displayed on the Fukusa.