Description

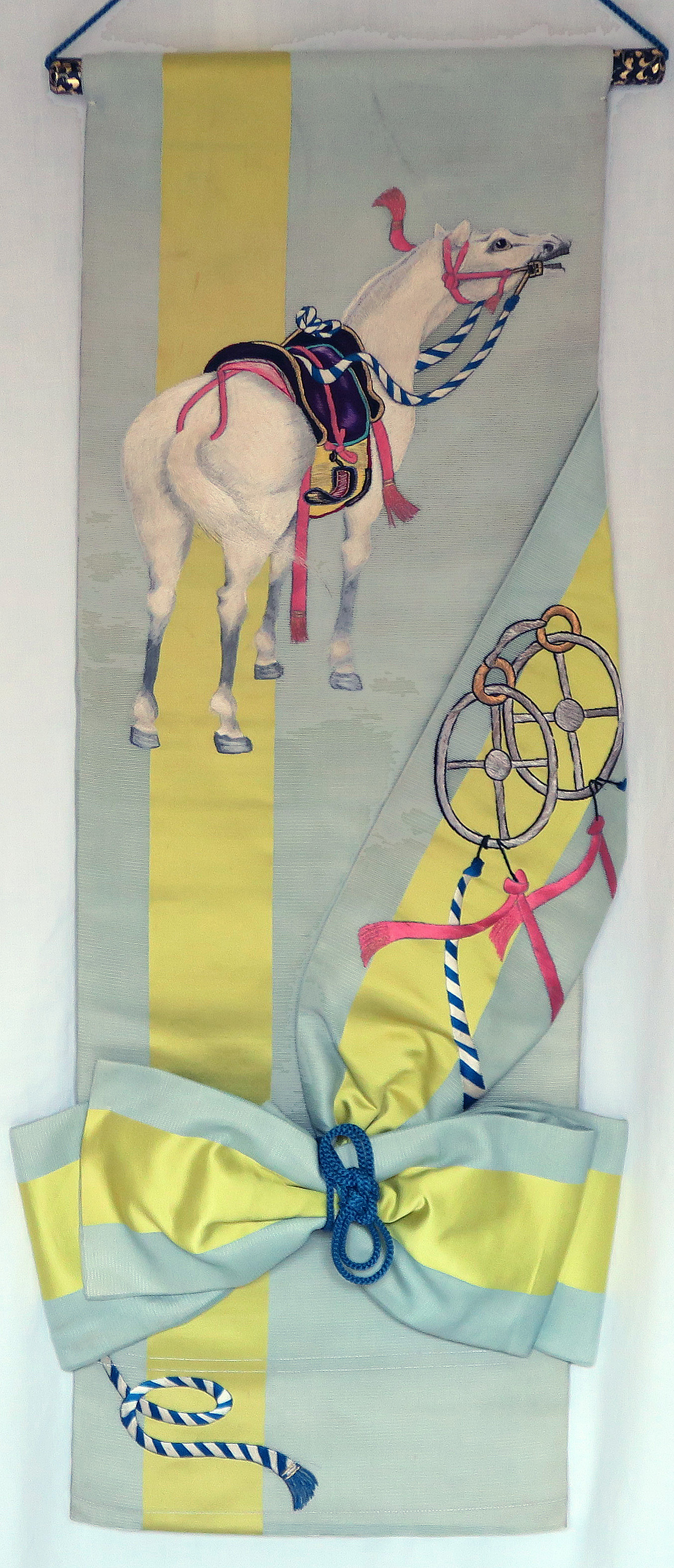

Finger weaving horse

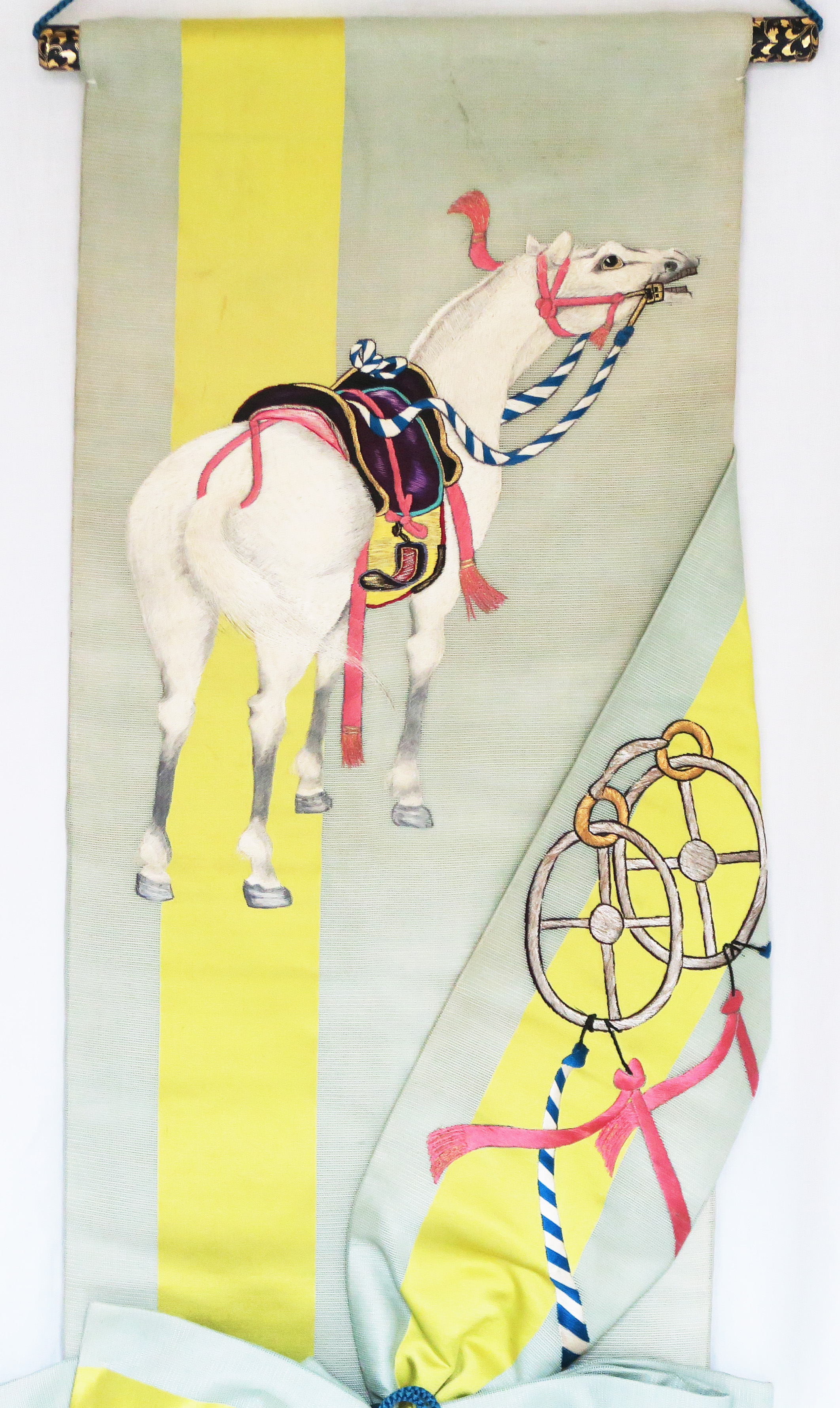

This elaborately hand woven work of fine art is also an example of the difficult skill of “Finger Weaving,” which makes this Obi appear to be embroidered; when, in reality, the design is part of the weaving from the very edge. This is a technique that is far more difficult and involved than embroidering an artwork after it has been woven. It takes a Master Weaver to create such a masterpiece. This weave is also referred to as “Tsuzure-Ori” or Tapestry weave. The weaver’s fingernails are the basic tools, used along with a wooden comb, with which he beats down and compacts the weft of the tapestry. Each nail has a shelf cut in it, which makes it resemble a step ladder…each step holding a different color of silk thread. This was what enabled the Master Weaver to create free-form designs. In this way, rare and sumptuous designs, resembling hand embroidery, were created for the nobility.

The use of a horse as the main motif demonstrated that it belonged to a woman of the nobility. Horses were limited to those whose ranking placed them within the circle of the Imperial Court. Over time, horses became associated with the Shinto Shrine and it became one’s heavenly duty to ride a horse when one visited the Shrine. The nobility were also expected to present meticulously groomed, luxuriously and decoratively trapped horses as gifts to the Shrine, while the poor were limited to giving paintings on wood (“Ema”) as their offerings. These can still be seen as valued works of art at many Shrines in Japan today, while the famous Nikko Shrine still maintains its white horses. These marvelous animals were most often used to lead the Shrine’s processions and were believed to bring or end rainfall.

The elaborately caparisoned horse (“Uma”) dominating this Nagoya Obi has been woven within the Summer Silk of the Obi. A garment woven of this gauze silk could only be worn in the summer months of June, July and August. It is an open mesh weave in which the strands of silk are twisted in the warp phase of the weaving; while the way these threads are interwoven determines the style of the weave. In this case, the style has been determined as “Summer Silk.”

It is, however, the finger weaving and the sophisticated presentation of the Caparisoned Horse that makes it absolutely unique. Only a Master Weaver could have created a textile such as this that goes from the sheerest of weaves right into the densely woven design of the Horse. It was a process that took much longer than traditionally woven textile art. It created rare and sumptuous designs for the upper classes who were the only ones who could afford to commission these masterpieces. Only natural dyes were used in this weaving, while the yellowish green color was known as “Moegi.”. Thus, the woman who wore this Obi would have been of high social standing as well as quite wealthy.

This wonderful Obi dates to the late Meiji Era (1868-1912), or the very early Twentieth Century.