Description

This striking image of the large flying Dragon (Ryu) on the back of this boy’s kimono is sophisticated and intriguing. It is also highly unusual, when compared with traditional boys’ kimono. The dragon is one of the most historically powerful images in Japan. Rather than inspiring terror, however, dragons carried a much more benevolent interpretation. The uplifting waves helped propel the dragon to the clouds (Kumo). There, the stylized cloud pattern, among which he flies, relieves him of the sins of the earth that he brought up with him. The dragon is one of four auspicious creatures and is especially revered by farmers as it is said that it controls the thunder and summons the rain.

The silk is hand woven and the dyes utilized in the Sumie Ink Painting of the dragon are natural. This version of the dragon, amidst the clouds flying over the spiking waves (Nami), has been very carefully applied using the Tsutsugaki method. This time and labor intensive technique required that all portions of the silk not accepting the dye had to be first painted out in rice paste. Once the painting was complete, the silk was washed over and over again in the local river water. The complex blending of the hues of black are a testament to the skill of the Master Artisan who painted this magnificent kimono which is a wondrous work of antique Japanese art.

The atmospheric landscape is similar to what can be seen on antique scrolls. It is not hard to believe that this commanding dragon, wending his way in sinuous splendor among the clouds (themselves considered auspicious) is full of remarkable powers. With its long whiskers hanging down from the side of its mouth, its fearsome claws, the surrounding blackness, and the strong and vigorous brush strokes, it appears both dreadful and sacred at the same time – almost like a deity. This is more true than not. With the introduction of Buddhism into Japan, the dragon incorporated those attributes of a guardian deity and was considered to be a protector of the land, its people and their crops. A similar symbolism holds true for Japan’s largest religious sect: Shintoism. In their mythology, the gods rode dragons to meetings at the Shrine of the Weather. In this way, they protected the inhabitants from fire and pestilence and were respected for their safeguarding of the crops. It is not surprising to find agricultural ceremonies in Japan that have been influenced by the dragon. The are considered “among the mos significant beings in Japanese lore.”

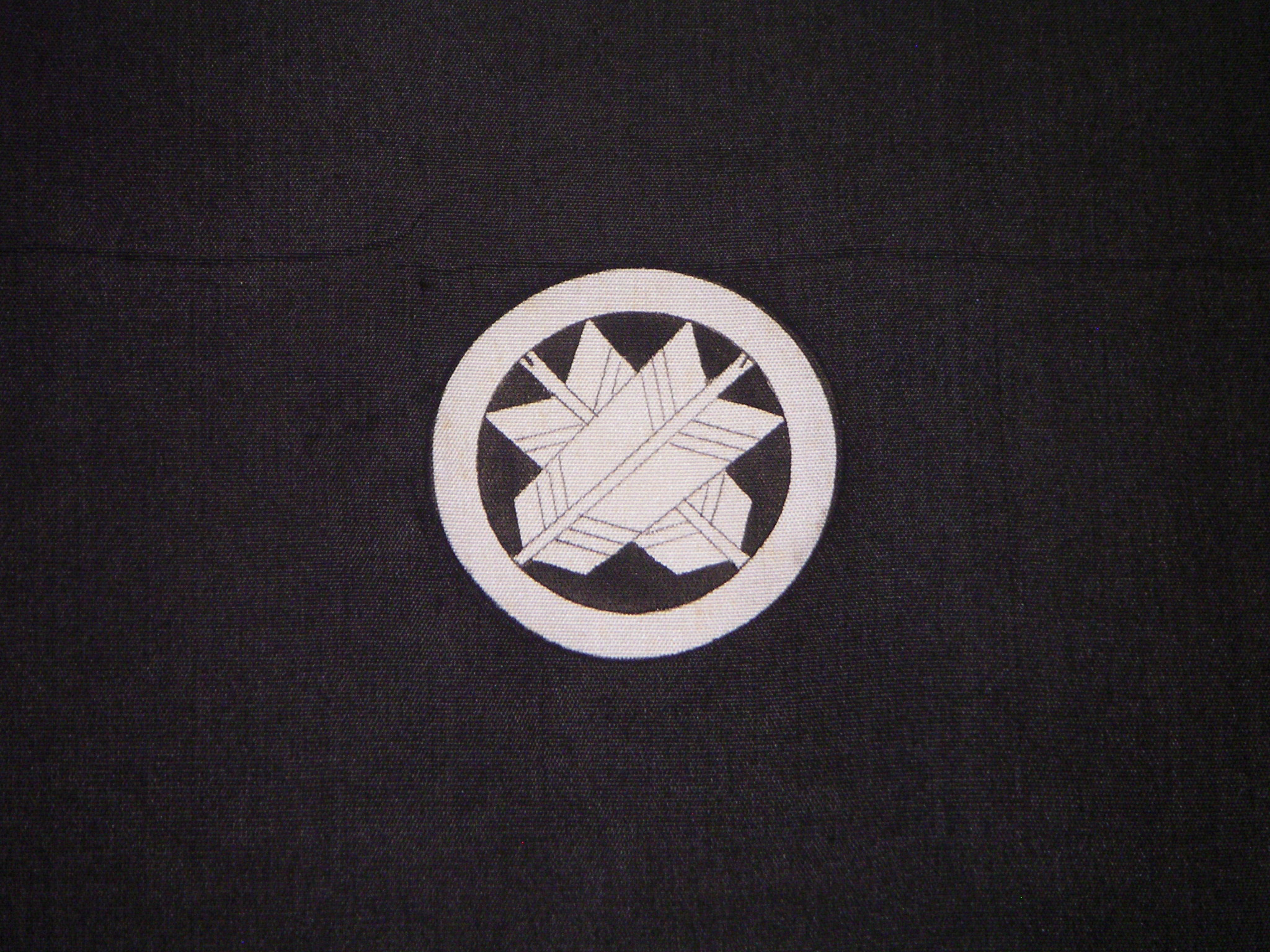

The family crest (Mon) that appears on the kimono is that of Crossed Feathers (Takanoha) within a dominant circle (Wa) or enclosure which had distinctive martial implications during feudal times. In Japanese heraldry, the feather would have been that of the Falcon (Hayabusa) which appeared first on the headgear of military leaders. In Japanese literature, the “way of the warrior” was often described as “the way of the bow and arrow” which lent itself, not only to warfare, but also to the popular pastime of archery among the upper classes. The circle itself came into being as a way to distinguish different branches of the same family from one another and was widely adopted by the end of the Tokugawa or Edo Era (1603-1867). In this fully lined kimono, the five versions of the crest indicate that this garment was worn for formal occasions.

The finer the skill of the expert artisan who created this masterful Kimono, the greater the status and wealth of the individual who commissioned the garment. This is a work of art that has remained a treasured heirloom for a member of the nobility for generations.