Description

DESCRIPTION: A Fukusa is a formal Gift Cover, designed and commissioned by a prominent family, used to cover an offering that has been placed on a wooden or lacquered tray during its elaborate and ceremonial presentation. Each aspect of the ritual was prescribed by closely defined rules of etiquette laid out during the Edo (1615-1868), Shogun or Tokugawa Era. The design was an original creation related to a specific use whose significance was handed down from generation to generation. The use of a Fukusa was an especially common practice prior to the 1900s, although it continues to this day in certain circles in Japan.

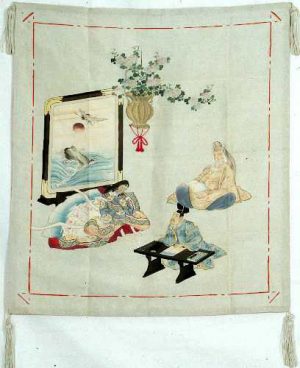

The painting illustrates a scene from The Tale of Genji, the world’s oldest novel written by Lady Murasaki Shikibu. The narrative describes the refined world of the inner circle of the highest class in the land during the Heian Era (794-1184), when the Emperor’s Court moved from Nara to Kyoto which was originally referred to as “Heian.” This fascinating genre picture exemplifies an elaborate landscape incorporating the carriage of a “Daimyo” or Lord, stopped by a stream bed, while he meets with an official looking “Bakufu,” an emissary of the Shogun’s government. In the foreground rests a gorgeously attired noble lady wearing the twelve kimono layers (“Juni Hitoe”) that exemplify her status by demonstrating the lack of need on her part to movement that this costume inspired. The dominant Pine (“Matsu”) denotes long life, while the lovely Iris (“Kakitsubata”) is the selection most celebrated in Japanese poetry and art. It denotes grace and beauty and has played a prominent role in Japanese cultural history, and is alluded to in The Tales of Ise, another famous literary classic

The silk of the Fukusa is a hard edged “Shioze Habutae” resulting from a warp faced plain weave fabric woven with thick wefts in which both warps and wefts are not glossed. It was then dyed and then hand painted in the “Tsutsugaki” or Rice Paste Resist technique. This process required tremendous skill as only one color could be painted at a time on the silk. The remaining colors were painted out in the rice paste while the original color was steamed, dried and then removed by rinsing it in the local river water. Each time a new color was added, including the background dye color; this same method would be utilized, entailing tedious and time consuming artistry.

The Fukusa was then embroidered and “Couched” with handmade pure gold threads. Each gold thread was created by painting liquid gold on a thin sheet of rice paper which was then rolled around a silk thread and cut lengthwise. Because this “thread” was so delicate, it was laid on top of the fabric and then hand stitched or couched to it. The back is a pattern on pattern silk weave that has been cut to match the exact size of the front of the Fukusa. It was then hand sewn on four sides creating a “Tachikiri Awase” Fukusa, the most formal Fukusa, defined by its sewing style. During the Meiji Era, only fifty percent were sewn in this manner. The basting threads were intended to keep the lining from showing when it was laid over the gift, while the four tassels weighed down the corners, fulfilling a sacred feeling of cleanliness as the gift was presented. The hand tied tassels have a classic five petaled plum blossom (“Ume Musubi”) knot, which, also, only graced fifty percent of the Fukusa of the Meiji Era.